Titanium white pigment: a metaphor for modern times.

Titanium white pigment: a metaphor for modern times.

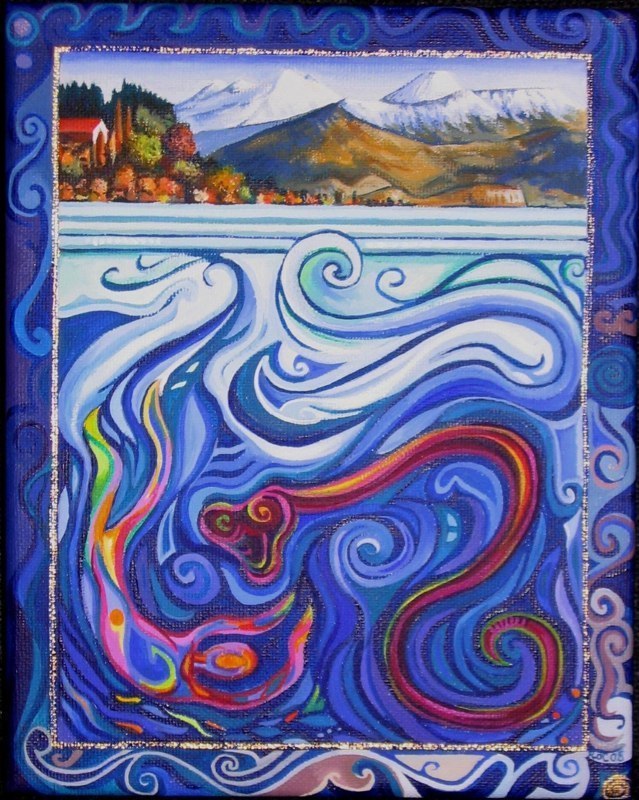

I learnt a very important lesson when I started to write religious icons do not use Titanium white for mixing especially for skin tones. If you do the colour becomes bland and greyish or at best Miami Vice pastel‚ as I call it. Instead Zinc white should be used as it mixes with other pigments and lightens and works with colours rather than overpowering them like Titanium white does. Zinc white is less opaque making the coloured undertones more nuanced to a greater degree than pigments mixed with Titanium.

Zinc oxide was first suggested as a pigment in 1782 while it wasn't until 1916 that Titanium white pigment suitable for artistic purposes was introduced replacing Lead white which had been restricted because of its toxicity 1. Titanium it seems has become the white pigment of our times.

Titanium white is used in writing/painting icons but only sparingly. Traditionally the very last thing an iconographer would do is apply the highlights to the eyes of the saint with Titanium. This is done on the edge of the iris but the pupil does not have a highlight for the figure portrayed ‚ is outside the condition of time.2 The true source of Light shines from Divine presence and permeates all things. This in itself suggests unity, balance and perfection which is what an icon should reveal.

Broadening out this theme of unity and balance consider practices, structures and political and economic systems which when left unchecked or when a mandate becomes too large have a negative or destructive effect on people and the environment.

In his book Columbus and other Cannibals‚ Jack D. Forbes describes the Native American term Wetiko as referring to a cannibal or, more specifically, to an evil person or spirit who terrorizes other creatures by means of terrible acts including cannibalism.3 Forbes then defines Cannibalism as the consuming of another life for ones own private purpose or profit.4 Cannibalism as defined by Forbes is not the literal eating of another mans flesh but rather is the act of consuming the other, their values, their culture, their land and their voice by a oppressive regime intent on overpowering and destroying for its own benefit. This destructive culture is understood as rife with sickness, Wetiko. A major symptom of Wetiko is greed particularly for wealth and power.

I don't agree with everything Forbes writes but I do appreciate what he says about the spread of this sickness. This greed for wealth and power is not a trait of one particular race or culture but rather can be found everywhere. But when this greed becomes normalised or excused a culture becomes unbalanced and the tilt towards the greedy results in the manifestation of huge social injustice, disempowerment, then eventually a slow emergence of simmering discontent and finally a full blown rage by the oppressed.

Also as a counter to the call for justice, some people in positions of power will use smear tactics and gross generalisations to undermine voices of dissent against greed and social injustice. Such tactics are the domain of the intellectually lazy and greedy. Their voice is in part motivated by a fear of loss, loss of wealth and status and yet calls for social and economic justice do not require this but rather ask for a system where people and nature are not chewed up and spat out for the benefit of a few. As we all know greed will always be part of this world but when the colours and diversity of this world become muted by a small overpowering element it becomes time to act.

Perhaps if we begin again to understand and believe in this world as an icon of beauty and that its mix of colour expresses a divine truth then we might begin to wake up from this slow destructive illness that can cloud our vision and harden our hearts. Titanium white has its place on the universal palette but only in small controlled applications.

1: Pigments through the Ages‚ www.webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/history/titaniumwhite.htm2: The Technique of Icon Painting‚ Guillem Ramos-Poqui, Morehouse Publishing, 19903: Columbus and other Cannibals‚ pg. 24 Jack D. Forbes Seven Stories Press 19794: Columbus and other Cannibals‚ pg. 24 Jack D. Forbes Seven Stories Press 1979