INTRODUCTION

"Almost everyone seems to agree that the times in which art tried to establish its autonomy - successfully or unsuccessfully - are over." (Groys. 2010 p. 39)"There can be no viable future for the world of human occupation unless it is able to sustain its inter-dependant condition of existence." (Fry. 2009 p.41)The Sachaqa[1] Art Centre in San Roque de Cumbaza, the Amazon highlands Peru established in 2010 by English artist Trina Brammah and her Peruvian husband Daniel Lerner is an organization with a mission[2]. Founded on principles of sustainability and environmental awareness the centre is a hub for visiting artists to learn about local art and craft practices by working with and learning from local people, experimenting with naturally and locally sourced materials and reconnecting with nature which includes using a long drop toilet, managing limited water and power supplies and refraining from working with materials deemed toxic or unsustainable. Visiting artist's can also meet with local shamans and participate in ceremonies, which involves the use of plant medicines including the hallucinogenic Ayahuasca.[3] The art and life of Shaman Pablo Amaringo (1938 - 2009) and Luis Tamani Amasifuen (1983 -) both Amazonian artists who paint extraordinary scenes from visions they have after drinking Ayahausca are also an influence and inspiration. Tamani lived in the village of San Roque de Cumbaza where Sachaqa is based. Trina Brammah also described herself as a visionary artist. In response to a question put to her on whether art can be sustainable and contemporary she replied,"Sustainable art for me is ‘Visionary art’ the visions received through shamanic journeying, meditation, the use of sacred medicine plants and dreams create a bridge to the ancestral world and the guardians and healers of our planet. ‘Contemporary’ is just a language, if you want to hold on to that language, hold on to it but make new world art with it."[4]The driving force to establish Sachaqa was a direct response to what the Brammah-Lerner's perceived as the global threat to the natural environment and the apparent loss of people's direct contact with nature and spiritual and shamanic practices.[5] This belief also encompasses the destruction of indigenous cultures, their knowledge and a belief in the interconnectedness of all life. This interconnectedness positions humans not at the apex of evolution but rather in the midst of it."The fundamental problem in the West today is the illusion of autonomy. It fails to recognize the interconnectedness of everyone and everything. And ignores the well-being of the whole." (Gablik, 2008, p.23.)The work by organizations like Sachaqa coincides with many other art organizations, movements, and artists who over the past few decades have sought to explore the question of how artists can "create work that is both ethically responsible" and still be "valid as art?"(Montag, 2008, p.7.) This also includes direct responses and critiques of environmental destruction, global warming and political and social injustices. This movement is vastly changed from the Land art movement of the 1960's, which initially did emerge from environmental concerns, but today can be critiqued as a continuation of the market driven art world, as land artists often relied heavily on wealthy patrons and the artwork itself often destroyed or altered the landscape it was created in. (Brown. 2014. p.11). Today artist's who come under the banner of eco-artists, or artists with a sustainable practice are challenged to not treat landscape like a giant canvas with a bulldozer for a brush (Roobard. 2006.) but rather to engage in the political, cultural, economic and for some spiritual elements of landscape.This essay will specifically focus on the work of three artists; Ana Mendieta whose work is a political, cultural and feminist critique of human ecology; Jason De Caires Taylor who incorporates science and conservation in his practice and Antonio Tapies who through mysticism and philosophy sought a different understanding of material matter which I suggest can challenge concepts of western consumerism. To conclude I will consider the work of art theorist T.J Demos who has written extensively on art and sustainability and will finish with a review of artist Avilo Forero’s A Tarapoto, un Manati recently exhibited in the “Rights to Nature” exhibition curated by Demos at Nottingham Contemporary.

ART & LANDSCAPE

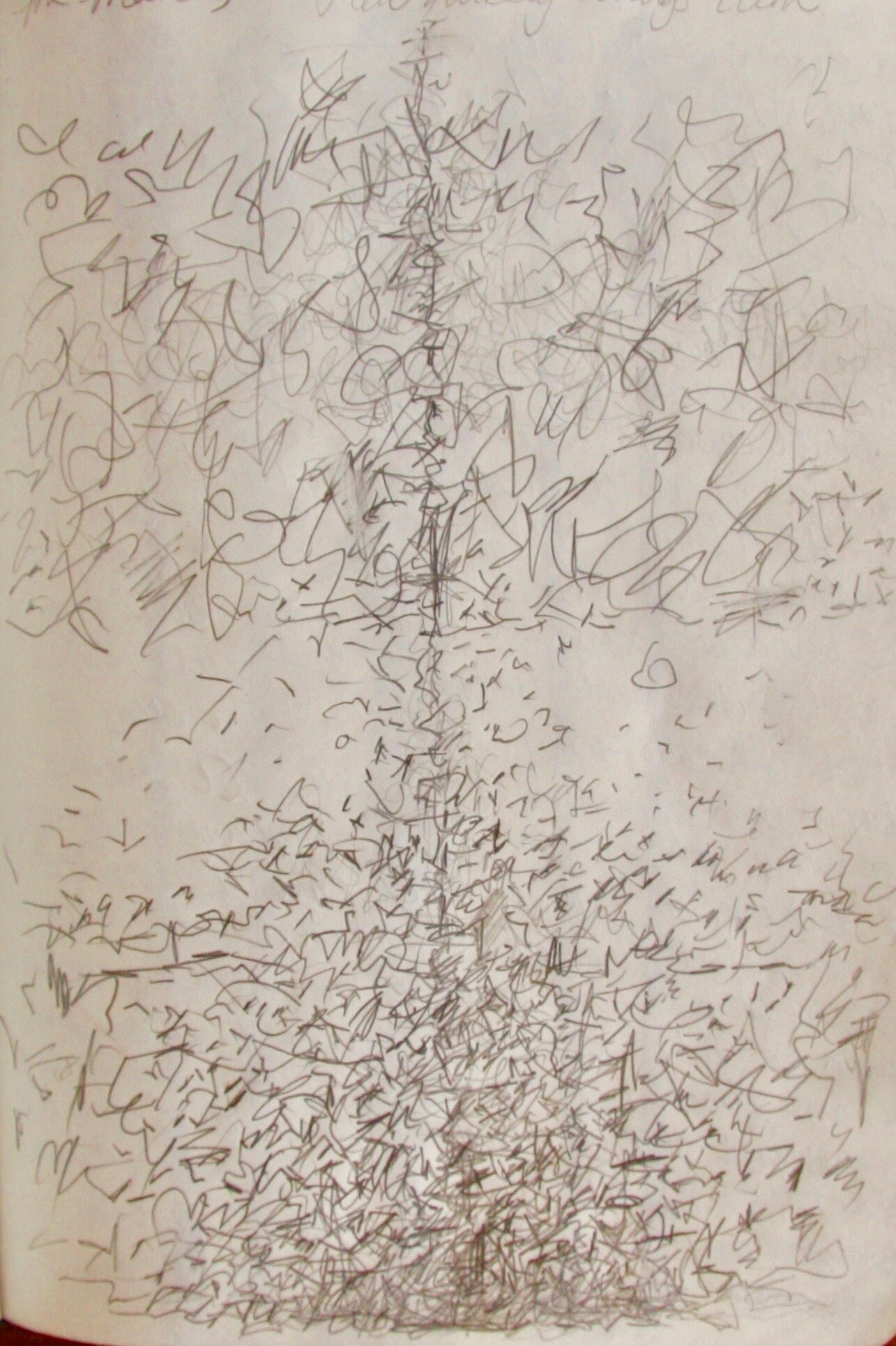

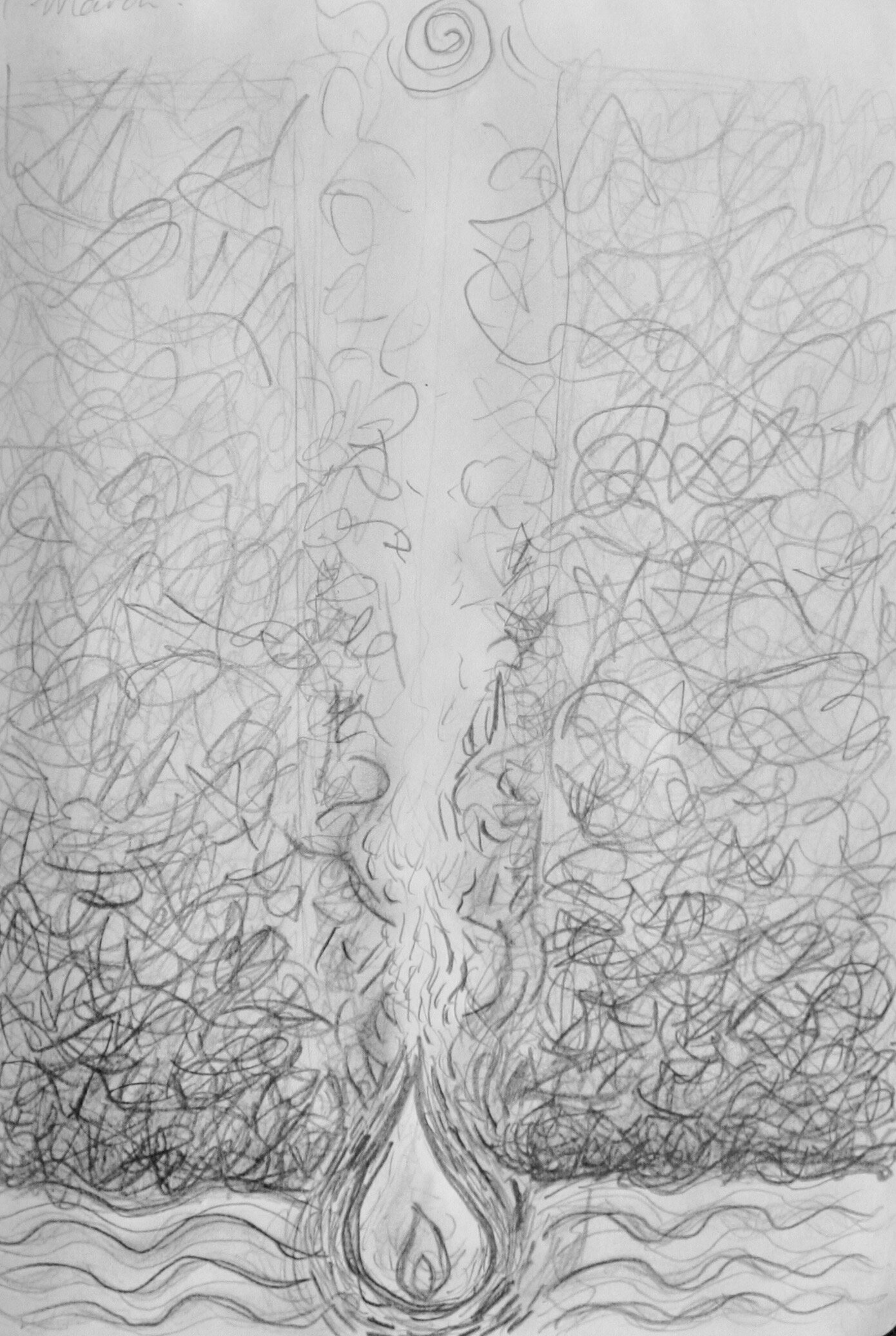

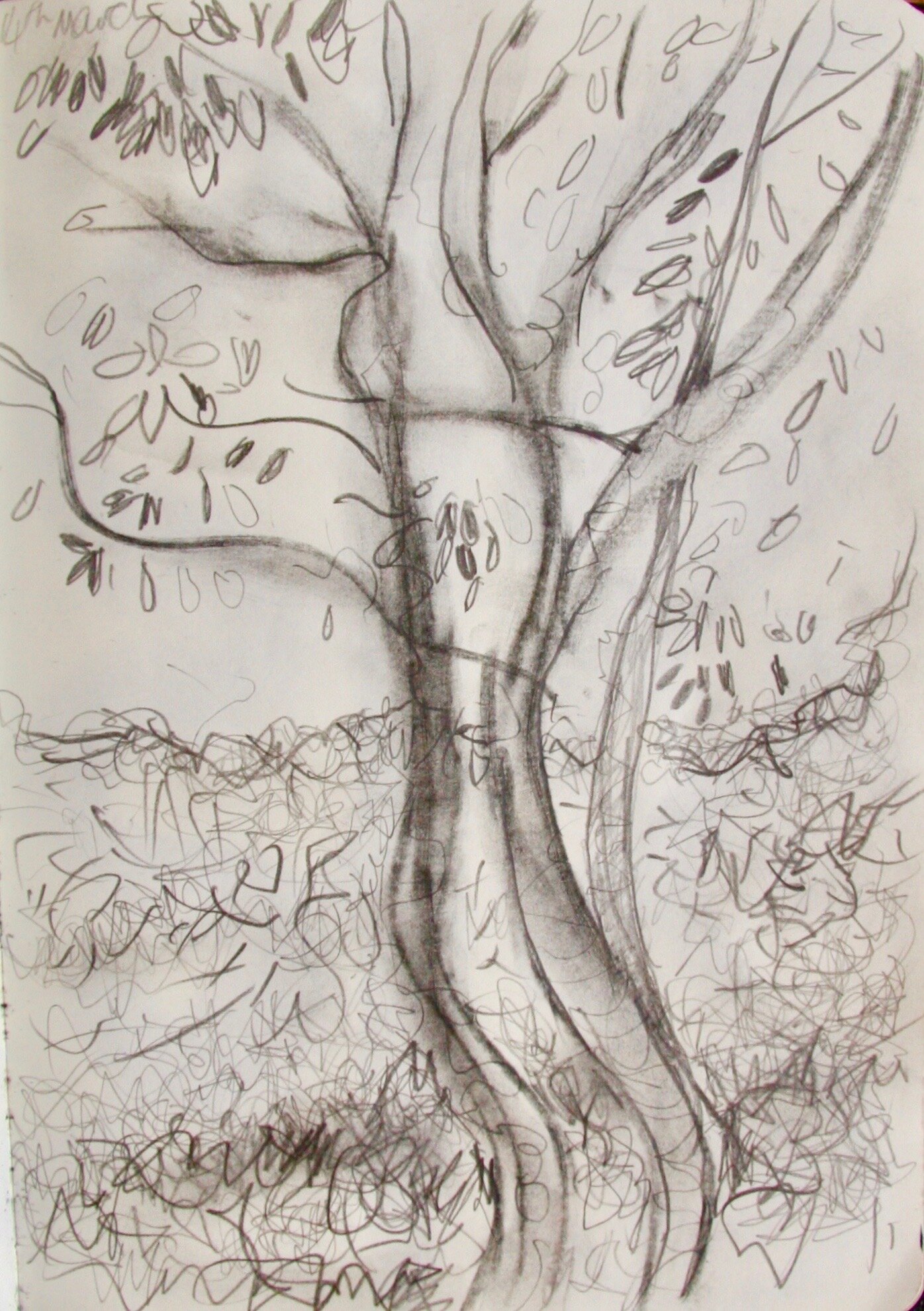

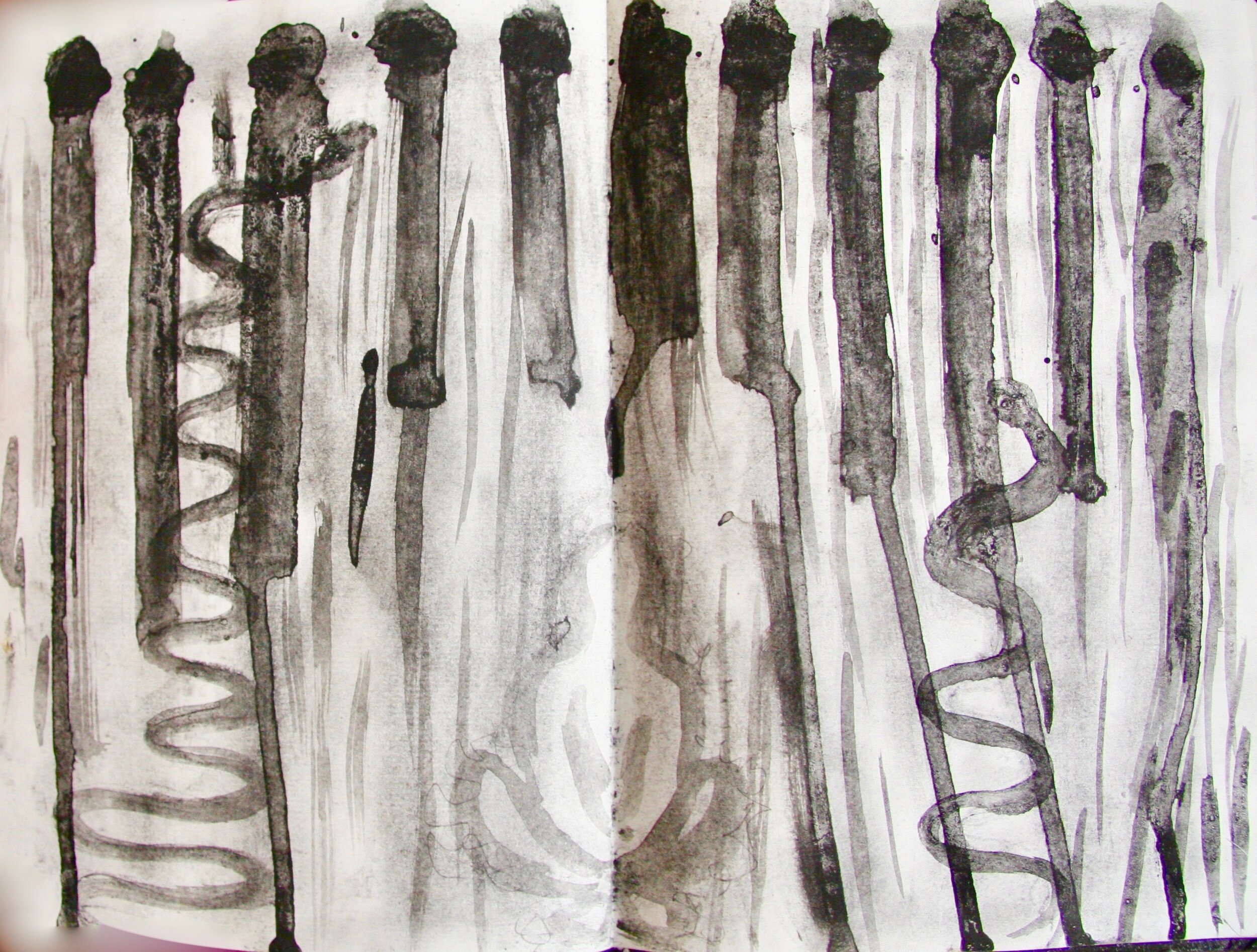

The Cuban Artist Ana Mendieta (1948 - 1985) used her body within landscape as a symbol of "the deep connection" she felt, "between landscape and the female body." (Rosenthal, 2013, p.11.)“My work is basically in the tradition of a Neolithic artist. It has very little to do with most earth art. I’m not interested in the formal qualities of my materials, but their emotional and sensual ones.” (Roulet, 2004, p.238.)Describing herself as a Neolithic artist Mendieta placed emphasis on the emotional and sensual qualities of her materials as a direct criticism of landscape artwork like Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty, "He brutalized nature" (Rosenthal, 2013, p.216.) and ongoing global environmental destruction. Mendieta's retrospective in the Hayward Gallery London 2013 revealed not only a large collection of artwork and archives but an integrated and methodical approach to an art practice that was political, socially active, environmentally aware and rooted in a deep connection with landscape. This rootedness perhaps in part made all the more pronounced through her experience of Diaspora was vividly portrayed in her Siluetea Works in Mexico 1973-77. In these works Mendieta used her own body or a silhouette to create in landscapes art that addressed issues of displacement and the degradation of woman and the environment. (MOCA. 2010). Mendieta's use of natural materials and film spoke of an ephemeral nature of art as well as the fragility of the landscapes she performed and created in.“The Siluetas demonstrate an attitude of care in relation to animate nature and advocate a kind of dwelling best described as touching the earth lightly: her marks on the landscape leave no permanent traces.” (Best, 2011, p. 107)Personally Mendieta's retrospective had a profound effect. I recalled my own childhood experience of living in New Zealand and the feelings of rawness I experienced as I traveled and lived through a landscape that had recently been deforested, drained and altered. Anger at short sighted and ignorant economic and political policies played out through the destruction of environments and cultures were and continue to be a factor in my own experience of exodus.The mission statement of Sachaqa Centro de Arte, promoting the necessity to share creative ideas and practices not harmful to the environment, and to work collaboratively with a political and social agenda, was a motivating factor for me to journey to the centre in 2013 for a two-month art residency. A strong interest, in conservation and political environmental organizations, my personal and familial experience of Maori art and culture[6] and a previous visit to the Amazon where I had experienced shamanic rituals and plant medicine were also influences. I had also spent seven years studying orthodox religious iconography and was captivated by the use of natural materials as well as the religious discipline required to write an icon[7] and icons liturgical and ritualistic functions. My art also involved working in the community art field, which, included projects exploring issues around sustainability, recycling, inequality and integration. I was also wrestling with ethical questions regarding my art practice and the wider contemporary art scene. Statistics such as "1 685 740 works of art are produced per day in the world. 19.51 works of art are produced per second in the world," (Keppi. 2009.) made me question the production of art as well as critique the market forces that drive much of today's contemporary art scene."We are weighed down by works of art! Their present-day number, which is practically infinite, already greatly exceeds our capacity for assimilation. Regardless, new ones are created everyday. How can we avoid contributing to this proliferation, without relinquishing the possibility of producing effects on the real? How can we progress without increasing?" (Farkas. 2009.)I didn't expect my stay in the Amazon to answer all my questions (let-alone counter balance the pollution caused by the flight!) but I hoped to explore an alternative to the theory of art as autonomous. My residency culminated in the creation of an installation titled "Aguaje Fire in the Belly" (O'Callaghan. 2013). Inspired by the Amazonian tree Aguaje it was created using local San Roque clay and Bombonaje palm and coloured with pigments sourced from the local Cumbazza River. I had chosen this tree as my inspiration as it is considered important culturally, spiritually and environmentally by the local people. The Aguaje fruit with its strange reptilian skin is sold in Amazon towns and villages. It is also made into juice and ice cream. The spines of the Aguaje tree are said to be in sorcerers' brews which when consumed help one see devils. The wood is used in construction and the trees are believed to attract water. The latter became the main theme of the installation as the region was experiencing an ongoing drought. Inside the installation were placed two Aguaje seeds. The installation was then left in a dry riverbed behind the art centre where open to the elements it would eventually break down and disintegrate releasing the seeds into the dry stream where they would hopefully sprout and grow.Moving beyond the traditional studio context and by incorporating locally sourced natural and biodegradable materials with an emphasis on the final piece disintegrating and disappearing I wanted to explore perceptions of ownership and production. Similar to Mendieta’s post-studio practice I wanted to touch the earth lightly. Art Historian Suzi Gablik writes, "The self-referencing discourse of modernism, with its unilateral focus on fine art, has become tedious and circular for many artists who now embrace post-studio practices." (Gablik 2008. p. 16.) Mendieta it can be said was visionary in the way she moved out of the studio and physically (literally) into landscape. Her work continues to reveal both a valid critical and ethical response to contemporary issues, which are even more pressing today. This is the challenge for 21st century artist’s who are faced with a myriad of political, cultural and environmental problems. The question still is how to respond?

Aguaje –Fire in the Belly Sachaqa Art Residency Amazon Highlands Peru 2013.

Photo Credit –Regan O’Callaghan

ART & POST-STUDIO PRACTICE

The work of British Guyanese artist and diving instructor, Jason de Caires Taylor (1974 -) is another challenging example of an artist’s post-studio practice. Taylor is famed for his underwater sculpture parks created by casting life size human figures in environmentally friendly materials, which actively promote coral growth. He has had huge international coverage for the projects he has worked on particularly the underwater museum “Silent Evolution” off the coast of Cancun, Mexico. Similar to Ana Mendieta, Taylor's practice takes on a multi-disciplinary approach that encompasses more than an autonomous theoretical understanding of art and is in contrast to the aesthetic objectives of land artists such as Christo and Jeanne Claude."Taylor’s art is like no other, a paradox of creation, constructed to be assimilated by the ocean and transformed from inert objects into living breathing coral reefs, portraying human intervention as both positive and life-encouraging. His pioneering public art projects are not only examples of successful marine conservations, but inspirational works of art that seek to encourage environmental awareness, instigate social change and lead us to appreciate the breathtaking natural beauty of the underwater world." (Yee. 2014.)Taylor's practice operates outside the traditional boundaries of contemporary art and studio practice but works within the framework of contemporary, issues. He also transcends the land-art of the 60's and 70's by working within landscape (or seascape in this instance) by creating art not purely influenced by an aesthetic and formal approach but also a scientific, artistic and sustainable one. In an interview Taylor said,"I am trying to portray how human intervention or interaction with nature can be positive and sustainable, an icon of how we can live in a symbiotic relationship with nature." (Pavone. 2012).This symbiotic relationship with nature stands in contrast to prevailing concepts, which still dictate nature is to be controlled for economic and political benefit. It also challenges the function of art as purely autonomous,[8] a function still being expounded in many art colleges, galleries and museums. Academic and artist Tim Collins explores this and states, "the current laboratory approach (gallery, museum, stage), where artwork is held in temporal and cultural stasis, then aesthetically examined, demands rethinking."(Collins. 2008. p.30) The creation of a new critical theory does demand the formulation of ideas, which, includes an active social, political and environmental mission but the artistic process of making obviously still needs to be incorporated. "Art was made before the emergence of capitalism and the art market, and will be made after they disappear." (Groys. 2010. p.18.)Nevertheless, the question of whether we still believe in a truly social and humane mission in art (Tapies. 1986. p.48.) is important. A visit to most contemporary art fairs might suggest the question is irrelevant. Also the emergence of eco-art, sustainable art or art that engages with the natural world doesn't dictate that all art should be made of hemp and or recycled trash or that the creation or production of objects is obsolete. Taylor however has transcended the traditional concept of the art market by creating living works of art. His museum off the coast of Isla Mujeres, Cancun, Mexico has become a huge tourist attraction not only for the visually stunning work he has created but also for the positive environmental impact it has had.

ART AND PRODUCTION

The Catalonian artist Antonio Tapies (1923 - 2012) whose own practice incorporated mysticism, philosophy, political activism and art theory sought to continually challenge the perception of art as autonomous but he also respected the process of making and selling work which included appreciation of the art market."It is unfair to claim that the marketing of objects of art (nowadays more often dismissed as 'trafficking') solely exists as a kind of commercial speculation. It may also be a response to a real spiritual necessity and be imbued with the spirit of dialogue, or exchange of values, or interesting emulation." (Tapies. 1986. p.125.)Primarily the exchange of ideas through the mechanism of art enables a "state of contemplation of reality at its deepest level." (Williamson. The Independent. 2012.) Tapies observation moves notions of spirituality and contemplation into the everyday and offers a mode of interpretation that is still relevant without necessarily being theistic. However there are questions as to whether Tapies constant artistic output undermined his call to re-evaluate ‘everyday’ material and in essence treat or see matter through spiritual glasses."Tàpies’s practice (and to an extent that of Burri) pushes towards what could be considered a form of mystical elementalism, in which the use of materials and references from outside the realms of fine art holds an intrinsic value of its own. Often discussed through the mist of terms like ‘alchemy’ or the ‘spiritual interconnection of matter’ this value is often framed as somehow separate from the visual parameters of the work – and as such from criticism." (Wiedel-Kaufmann 2013.)Wiedel-Kaufmann raises an interesting point with regards Tapies and how artists and (within the context of this essay) the art market have cleverly used esoteric notions to ignore critical and perhaps ethical questions.“In imbuing his materials with a spiritual purpose Tàpies seems to have neglected the visual potential of his practice and in so doing pushed towards the monotony of a production line. For whilst all the best art of course approaches a notion of alchemy – in its transcendence of rationally explicable inputs – one cannot help but think that a more critically accessible conception of his own practice would have aided Tàpies’ development. (Wiedel-Kaufmann 2013.)Damien Hirst a former catholic and now a declared atheist whose studio has produced over 6000 paintings[9] many inspired by themes of death and religion has also been criticized for mass production and manipulating the art market for his own benefit. However in defense of Tapies it can be said the Catalan artist was not motivated by the market nor did he “filch”[10] ideas but rather his practice and understanding were informed by a deep sense of political and social justice not just a spiritual or quasi spiritual approach to the art market and his essays are an attempt to critically engage with what Tapies considered a fundamental aspect of art and that is its engagement with a wider world not just a white walled gallery.“Tàpies offers us a ‘materialist’ vision of the world. His message focuses on a revaluation of the low, the repulsive, of material… Material is the substantial element of life. One consequence of that rejection of the idea in favor of material is the notion of the ‘formless’ whose aim, according to Georges Bataille, was to cancel out all formal categories: the ‘formless’ cancels out the distinction between nature and culture. ..." (Fundacion Antoni Tapies 2015.)Recent critical thought still suggests the contemporary art scene in-practice does little to challenge the illusion of the west's projection of autonomy but rather colludes with it. While on one hand having banished the spiritual, magic or mystery of art to the realms of the deluded the art market also cleverly projects and promotes the myth of the autonomous neo-talisman for huge economic gain. Thus is the production of art objects in itself really questionable? For example artists like Balint Szombathy are "not overly concerned with adding to the global stockpile of art pieces or material objects of any kind, since for the artist, ‘creativity is not connected with production, but rather with establishing ‘models of new linguistic systems'". (Fowkes. 2012.) What then, is the relevant question the ethical or sustainable production of art or how the viewer or the consumer engages with art or object?While it can be argued that art with ecological themes have become more mainstream (Brown 2014. p.6), issues of sustainability and the environment within the contemporary art market have overall little engagement and or effect. For this to happen a new critical theory is needed.

A NEW CRITICAL THEORY

"Critical practice in art can be defined as an ethically based, conceptually grounded approach that addresses the social sphere from a position of critique and does so by embracing process as well as product and involving multiple constituencies, sites of production, and strategies for collaboration." (Smith 2005. p.15)A new critical theory could dismantle the foundations of the ever expanding and booming art market. Critiquing the contemporary art market would also require analyzing the burgeoning eco art/sustainable art movement, which it can be argued operates in-part within the traditional setting of gallery, museum, transport, advertising, storage and consumption. Cultural critic and art historian T.J Demos asks,"How can art oppose the commercialization of nature, packaged as economic resource, or redirect commercial forces in favor of alternative ways of defining the environment and sustainability with a focus on global justice? How might artists, furthermore, animate an ‘environmentalism of the poor’ – meaning environmental justice viewed from the perspective of those who have the least access to resources, job protection, socio-political and economic equality and governmental and media representation - to avoid the exclusivity of ‘environmentalism born of affluence’ in Western capitalist societies?" (Demos. 2009. p.24.)It became apparent to me very early on in my residency at Sachaqa that environmentalism born of affluence is very much alive and kicking and I was a part of it. However, where I felt the work of the centre was beneficial was in the collaborative way it engaged with the local community and how it celebrated and respected the practices of the local artists and artisans. Fundamentally it was this collaboration that spoke most directly to me about a way forward for my own art practice as well as suggesting a model of practice that could fit elsewhere. Sachaqa's mode of operation worked at and encouraged collaboration between people. It advocated locally sourced materials and art and craft thus assisting the continuation of traditions. It enabled a multi-disciplinary approach towards art practices that incorporated a wider sphere of influence. It challenged perceptions of art for art's sake and in the process rekindled a notion or belief in the use of art. By use I mean a relationship with art that moves beyond the gallery or museum. It critiqued formal aesthetic theory by its understanding of 'visionary art' and it also questioned western capitalist notions of value, power and truth.In the exhibition Rights of Nature – Art and Ecology in the Americas[11] curated by TJ Demos and Alex Farquharson, the issues facing not only contemporary western art but the natural environment and the globe were explicitly raised and explored through the work of 20 artists from the Americas. Themes of sustainability, indigenous culture and legal and political reform were explored through this “research intensive exhibition”. (Aesthetica. 2015.) Specifically the collection highlighted the movement in the Americas where artists are working collaboratively across the political, cultural and religious spectrum with indigenous cultures, environmental organizations and charities, legal reformers for land rights and the rights of nature.“The Americas, in particular, are the site of intense legal, political, and cultural activity that links indigenous movements, political activists, legal theorists and ecologically-concerned artists. Bolivia and Ecuador have recently enshrined the rights of Mother Earth in their constitutions and legal systems. A cultural-political- philosophical revolution is redefining our relationship to the world. ” (Nottingham Contemporary. 2015 Catalogue p.2.)Artist’s involvement within this political movement in the America’s may offer some different insights and opportunities particularly as it is seems a European equivalent does not have the same momentum or collegiality. In the America’s it appears belief in a collective humanity or ‘interconnectedness’, is a driving force behind the movement, bringing together a diverse group of peoples, organizations and political, religious, legal and artistic movements. In Ecuador and Bolivia this belief has manifested in new laws, which encapsulates the common cause. The Law of the Rights of Mother Earth[12] by the Bolivian Government places a challenging counter narrative to Western European concepts of humankind’s positioning in the world. It declares -“We are all part of Mother Earth, an indivisible, living community of interrelated and interdependent beings with a common destiny; gratefully acknowledging that Mother Earth is the source of life, nourishment and learning and provides everything we need to live well; recognizing that the capitalist system and all forms of depredation, exploitation, abuse and contamination have caused great destruction, degradation and disruption of Mother Earth, putting life as we know it today at risk through phenomena such as climate change; convinced that in an interdependent living community it is not possible to recognize the rights of only human beings without causing an imbalance within Mother Earth; affirming that to guarantee human rights it is necessary to recognize and defend the rights of Mother Earth and all beings in her and that there are existing cultures, practices and laws that do so; conscious of the urgency of taking decisive, collective action to transform structures and systems that cause climate change and other threats to Mother Earth; proclaim this Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth, and call on the General Assembly of the United Nation to adopt it, as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations of the world, and to the end that every individual and institution takes responsibility for promoting through teaching, education, and consciousness raising, respect for the rights recognized in this Declaration and ensure through prompt and progressive measures and mechanisms, national and international, their universal and effective recognition and observance among all peoples and States in the world. “ (Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth 2010. Preamble.)This bold statement has revolutionized peoples to respond globally to what is seen as a threat to humankind’s very existence. The call for a raised consciousness is also found in the writings of Swiss Psychiatrist C.G Jung who considered the “collective unconscious, (as) in no way an abstract concept, but a living reality.” (Sabini. 2008. P.14). Similarly Jung believed humanity and nature including inanimate matter shared the same consciousness[13].In art and within the context of this essay this reinterpreting or reminding of humankinds relationship with non-human matter has been seen as fundamental. The values and theories of Tapies who critiqued the relationship and value of matter, Mendieta whose interest lay in the emotional and sensual qualities of matter rather than its formal qualities and De Caires Taylor who was influenced not by a purely aesthetic approach to matter but by a scientific, artistic and sustainable one are all intrinsic to the ongoing development of a critical art theory of sustainability. All three artists have revealed a thought process and engagement with their art that transcends notions of autonomy while at the same time not denying artistic production. However without issuing blame the question still needs to be asked have any of these theories and art practices been enough to encourage the push towards a more sustainable approach in art and art practice? Despite their pledge the Bolivian Government is now allowing and encouraging oil and gas drilling in areas of natural, cultural and spiritual significance to local tribes (Miroff. 2014). The art market continues to prosper and grow and the magic of autonomy still attracts and excites big investors while thrilled visitors continue to flock to ever expanding art collections in museums and galleries. Nevertheless, the continued push by artists through practice led research to ask questions of these ongoing issues is fundamental. Exhibitions focusing on art and ecology do remain important and urgent at this time.[14]“To contribute to the ongoing public engagement with the politics of sustainability, to advance creative proposals for alternative forms of life based on environmental justice in a global framework, and to do so until such art exhibitions can somehow meet the requirements of a just sustainability – these are the imperatives for a contemporary environmental art.“ (Demos. 2009. p.28.)

CONCLUSION

The work of Colombian/French artist Marcos Avila Forero (1983 -) who exhibited in “Rights of Nature” often uses simple concepts and devices of memory and storytelling as a way in which to share and promote his concerns about the environment and social justice. His work A Tarapoto, un Manati[15] recounts a legend the artist had heard about the manatee, a large aquatic mammal that has virtually disappeared from Amazonian rivers. Forero traced the journey of a young Amazonian Shaman who had carved a wooden canoe in the shape of the manatee. The meandering footage of the canoeing shaman takes the viewer on a journey up the Amazon River past riverside townships into scenes of nature finally ending in Lake Tarapoto. The manatee is believed a sacred animal in the Amazon. By taking the legend of the manatee Forero weaved together a clever critique of the post-modern world by using story and memory as a “re-activator” (Forero, 2011). As the young shaman traveled up the river away from civilization paddling his wooden manatee the film is a reminder of the ebb and flow and cycles of nature and how humankind is part of that cycle. The artist interviewed -“Today, objects and ideas, as do people, travel constantly and rapidly. How do we conceive each social reality, how do perceptions, people and things, in traveling, become transformed in this constant flow?” (Forero. 2013)Forero speaks of the rapid movement and change that has occurred within social, cultural and political realms while at the same time calling for peoples to remember their past and consider their future.“His work is politically compromised and gives testimony of complex realities that are sometimes also violent. He is the artist-ethnographer. The work re-represents (re-enact) quotidian experiences through performance, which the artist understands as alternative to history and memory that engages and transports the viewer beyond boarders, places and time.” (Wall Street International 2015.)His emphasis on an object (the wooden manatee) and how man relates to it is a clever political device used to imprint a visualization without being preachy or esoteric. The slow paddling of the manatee canoe also relates to the simple everyday processes, journeys and rituals we all make often without thinking. In a similar vein the Swiss video artist Pippilotti Rist uses the ritual of the mundane with creative effect to remind and recall. “I think about the shared rituals we need and those we should not allow to disappear. I'm interested in bodily presence and try to increase the manifold possibilities of movement of my objects and living beings.” (Rist. 2007. P.21). Forero places people and objects in spaces of tranquility and also loss and violence. Using these themes he works collaboratively with communities, artisans, peasants, and craftsmen, in order to create his work and give voice to their concerns and issues. Using locally sourced materials from nature he creates new objects or re-creates/transforms existing objects into tools of expression and memory or meta-memory. Forero expresses the imperatives that Demos believes are instrumental to the ongoing dialogue and development between contemporary art and sustainability. These are engagement with political theories of sustainability, advancing the cause and offering creative alternatives to challenge the status quo.It could be said a huge paradigm shift is needed by the contemporary art world before it can even acknowledge the pressing concerns of global warming and environmental destruction. However the artists and theorists who continue to practice and produce art while holding to ethical and social values clearly show the movement towards a sustainable future is not only possible but fundamental. The initial three artist’s referenced in this essay have each contributed to social and political discourse. Forero along with many others continue this work by reminding through critical thought and practice the urgent need to address the paramount and pressing concerns of global environmental destruction.“Just as nature can no longer be understood as a pristine and discrete realm apart from human activity, art’s autonomy is all the more untenable when faced with ecological catastrophe.” (Demos 2012. P. 197).Art as autonomous is defunct. New theories of art and other models of trade are needed which are just and sustainable. The commodification of natural resources has resulted in inequality and environmental destruction and the contemporary art market is part of this monolithic conglomerate. It is here artists can be facilitators working together with different groups, indigenous peoples, lawyers, conservationists, to bring about a new narrative which still celebrates and promotes creativity while at the same time being politically and socially engaged and sustainable in practice.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aesthetica 2015. Review Rights of Nature. http://www.aestheticamagazine.com/rights-nature-art-ecology-americas-nottingham-contemporary-nottingham/Best, S. 2011. Visualizing Feeling: Affect and the Feminine Avant-Garde. I.B. Publishers.Brown, A. 2014. Art And Ecology Now. Thames & Hudson.Charing, H. Cloudsley, P. Amaringo, P. 2011. The Ayahausca Visions of Pablo Amaringo. Hinner Traditions International.Collins, T. 2008. Catalytic Aesthetics. Artful Ecologies. Falmouth University PressDemos, T. J. 2009. The Politics of Sustainability: Contemporary Art and Ecology - Radical Nature: Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet 1969–2009. Published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name, shown at the Barbican Art Gallery, edited by Francesco Manacorda, 16–30. London: Barbican Art Gallery.Demos, T.J. 2012. Art after Nature. ArtForum Magazine. April 2012.Farkas,J.B2009 http://artandsustainability.wordpress.com/2009/11/24/the-growing-stockpile-of-contemporary-art-2/Forero, M. 2011. http://www.newfolder.fr/en/marcos-avila-forero/Fowkes, M & R. 2012. Signs of the City under Erasure. http://www.translocal.org/translocalold/writings/balint.htmlFry, T. 2009. Design Futuring. Burg PressFundacion Antoni Tapies 2015 http://www.fundaciotapies.org/site/spip.php?rubrique80Gablik, S. 2008. Art and the Big Picture. An essay in Artful Ecologies. University College Falmouth.Groys, B. 2010. Going Places Sternberg Press.Jung, C.G. 1970. Civilization in Transition - Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Edited by Adler, G., Princeton University Press.Kehoe, A. 2000. Shamans and religion: An Anthropological Exploration in Critical Thinking. Waveland Press.Keppi, C. 2009. http://jbf.biennaledeparis.org/en/index.htmlMiroff, N. 2014. Gas Boom in Bolivia brings new wealth and regrets for a lost opportunity. Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/gas-boom-in-bolivia-brings-new-wealth--and-regrets-foralostopportunity/2014/11/14/1e229f4e-2a02-4119-9498-4a899a5ff8fb_story.htmlMOCA 2010. The Museum of Contemporary Art. Los Angeles http://www.moca.org/pc/viewArtWork.php?id=87Montag, D. 2008. Artful Ecologies. University College Falmouth.Narby, J. 1998. The Cosmic Serpent - DNA and the Origins of Knowledge. Phoenix 1998.Pavone, P. 2012. Interview with Jason DeCaires Taylor http://scribol.com/art-and-design/an-interview-with-underwater-sculptor-jason-decaires-taylorO'Callaghan, R. 2013. http://www.reganocallaghan.com/?page_id=68Rist, P. 2007. Congratulations. Published in conjunction with the exhibition Gravity, Be my Friend. Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall.Roobarb. 2006. The Principles of Sustainability in Contemporary Artttps://artandsustainability.wordpress.com/2006/06/01/the-principles-of-sustainability-in-contemporary-art/Rosenthal, S. 2013. Ana Mendieta: Traces. Taken from a conversation between Mendieta and Marta, J. February 1985 Hayward Publishing.Roulet, L. 2004. Ana Mendieta: A Life in Context. Exh. Cat. Washington Hirshorn Museum.Sabini, M. 2008. The Earth has a Soul. C.G Jung on Nature Technology and Modern Life. North Atlantic Books.Smith, S. 2015. Beyond Green. University of Chicago 2005.Tapies, A. 1986. Selected Essays. Van AbbemuseumUniversal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth 2010 April 22, World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth Cochabamba, Bolivia. http://www.worldfuturefund.org/Projects/Indicators/motherearthbolivia.htmlWall Street International. 2015. Marcos Ávila Forero. Paisajes Revoltosos.http://wsimag.com/es/arte/13175-marcos-avila-forero-paisajes-revoltososWiedel-Kaufmann, B. 2013. Antoni Tapies Abstract Critical http://www.abstractcritical.com/article/antoni-tapies/index.htmlWilliamson, M. Obituary Antonio Tapies. Independent Newspaper. 8th Feb 2012. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/antoni-tapies-catalan-artist-celebrated-for-his-use-of-found-materials-6649501.htmlYee, C. 2014. Underwater sculptures with meaning and purpose. IRESEARCH https://iresearchpro.wordpress.com/2014/10/23/underwater-sculptures-with-meaning-purpose/

[1] Sachaqa translates as 'Spirit of the forest in Quechuan.

[2]"Our Mission and Vision - To provide affordable creative space and accommodation for sculptors, painters, musicians, ceramicists, textile artists, writers, dancers, etc.

To have regular

exhibitions, showing all types of media including two-dimensional works, sculpture, video, and more in the city of Tarapoto, Lamas and San Roque. To learn and exchange creative ideas and techniques with local artist and artisans.

To look for alternative creative methods that are not harmful to the environment. We aspire to learn to respect Mother Nature and be conscious of her in all that we do. This means that everything is recycled and there will be no chemicals/pollution going into her rivers. We must be conscious of the clothes that we wear, washing powders, hair and body soaps, lotions and the food that we eat. Harmful chemicals that exist in these products can have a very direct effect on our environment." http://www.sachaqacentrodearte.com

[3] "Amazonian shamans have been preparing Ayahuasca for millennia. The brew is a necessary combination of two plants, which must be boiled together for hours. The first contains a hallucinogenic substance, dimethyltryptamine, which also seems to be secreted by the human brain; but this hallucinogen has no effect when swallowed, because a stomach enzyme called monoamine oxidase blocks it. The second plant, however, contains several substances that inactivate this precise stomach enzyme, allowing the hallucinogen to reach the brain." Narby, J. 1998.

The Cosmic Serpent - DNA and the Origins of Knowledge. Phoenix p.10.

[4] Trina Brammah interviewed by Regan O'Callaghan. 17th July 2014.

[5]Anthropologist Alice Kehoe criticizes the generalized term 'Shaman' in her book Shamans and religion: An Anthropological Exploration in Critical Thinking. Waveland Press 2000. In the context of this essay my use of the term refers to Amazonian shamans particularly of the Shipibo Tribe from the Pucallpa region that lead Ayahuasca medicine ceremonies.

[6] My lineage descends from Ngati Tuhourangi a sub-tribe of Te Arawa, a Maori tribe that comes from the geothermal central plateau region of the North Island, New Zealand.

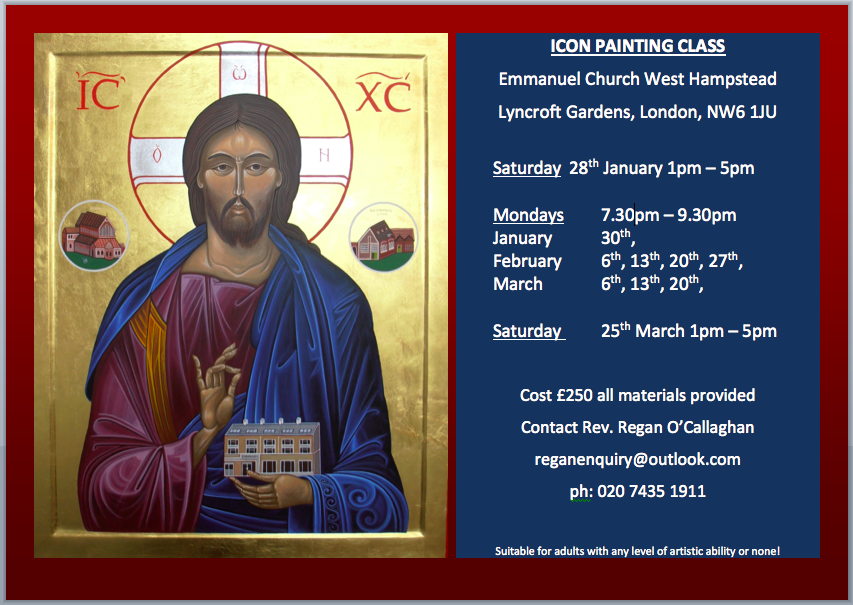

[7] Traditionally a religious icon is written rather than painted. Icons are not understood as art but rather visual sermons or prayer so just as a priest may write a sermon to preach verbally so an icon is written to preach visually.

[8]"The equivocation that is typical of art, curatorial activity and criticism do not serve us as well as they did at the turn of the 20th century. Where it might have been a radical act 100 years ago to claim autonomous heteronomy, today this position simply reinforces the artist's role in the past, as a condition of today. Used as a validating principle it is increasingly a point of constraint rather than a path to help us develop and understand new theory and its relationship to practice." Collins, T. 2008.

Catalytic Aesthetics artful Ecologies. University of Falmouth p.41.

[9] Damien Hirst: ‘

What have I done? I’ve created a monster’. Interview in the Guardian Newspaper 30

th June 2015. Catherine Mayer.

[10] Damien Hirst: ‘

What have I done? I’ve created a monster’. Interview in the Guardian Newspaper 30

th June 2015. Catherine Mayer.

[11] Rights of Nature Nottingham Contemporary 24

th January to 15

th March 2015. Curated by Demos T.J, and Alex Farquharson with Irene Aristizabel.

[12] Law of the Rights of Mother Earth is a

Bolivian law that was passed by Bolivia's Plurinational Legislative Assembly in December 2010. The law defines

Mother Earth as "a collective subject of public interest," (Article 1 line 3) and declares both Mother Earth and life-systems (which combine human communities and eco-systems) as titleholders of inherent rights specified in the law.

[13] “No man lives within his own psychic sphere like a snail in its shell, separated from everybody else, but is connected with his fellow-men by his unconscious humanity. “ (Jung. Civilization in Transition par 408.)

[15] A Tarapoto, un Manati 2011Video installation: HD Projection and CRT. 18 mins. Forero M.